For many, ‘sovereign cloud’ was the IT buzzword of 2025. Will 2026 be the year that sovereign cloud moves from talking point to widespread adoption? Below, I make three predictions for how the European market for sovereign cloud services will develop in the year ahead.

- Despite all the hype, US hyperscalers will dominate the European market for cloud infrastructure services in 2026

Europeans have been adopting US public cloud services since AWS launched its S3 offering in Europe in 2007. As of 2025, three US cloud providers held 70% of the European market for cloud infrastructure services; European providers held a mere 15%.

That said, there is significant demand for European sovereign clouds. A recent survey of CIOs and IT leaders in Western Europe found that 60% want to increase their use of local cloud providers. The total European market for sovereign cloud services is projected to grow from just over EUR 20bn in annual revenue today, to over EUR 100bn in 2031.

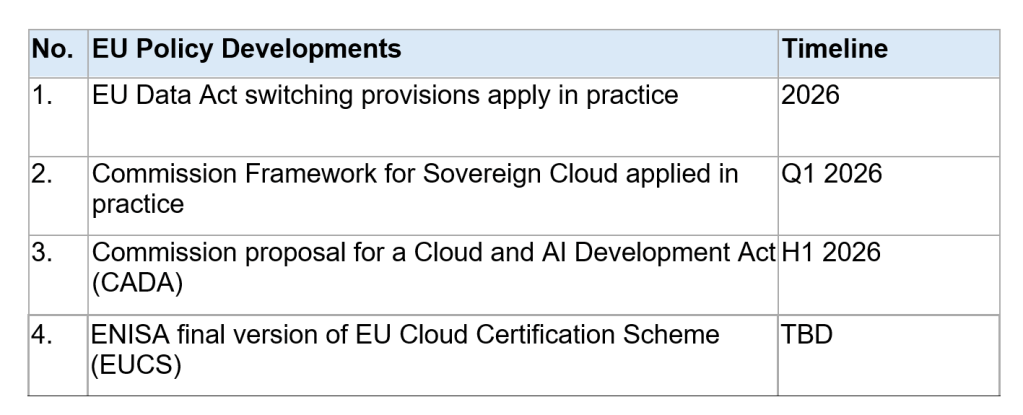

Yet despite the increased demand for European sovereign clouds, the US hyperscalers’ market share is unlikely to decrease dramatically in the short term. This is, in part, due to the cost and complexity of switching. Porting data from one cloud service to another is often technically challenging due to large data volumes and proprietary data formats. Since September 2025, the EU Data Act has required cloud providers to support switching, including by reducing technical barriers. It will be interesting to see whether these new obligations make it easier for customers to switch cloud providers in 2026.

Cloud customers can also face organisational obstacles to switching, as business processes are based on familiar, industry-standard software applications. Many Europeans would probably be happy to use a European cloud, provided they can still work in Microsoft Word, PowerPoint, and Excel. By contrast, switching to a full Euro-Stack, with only European or open-source software might disrupt business operations. What’s more, Europeans will want access to the latest AI services, many of which are provided by US companies.

Partnerships between US and European providers can help, by offering access to US software running on European-managed servers, as with S3NS and Bleu in France and Delos and Sovereign OpenAI in Germany. Despite European providers investing in AI infrastructure in 2026, the US hyperscalers remain well placed to provide cloud infrastructure for AI model training and inference. While France’s Mistral is investing in its own infrastructure, it also has a partnership with Microsoft for use of the latter’s GPUs.

Lastly, not all European organisations want to use European clouds. Many may believe that US intelligence agencies are simply not interested in the kinds of data they process. Equally, they may consider it unlikely that the US would actually impose sanctions on them that impede their access to the cloud. As a result, they assess the risk of using US cloud providers to be acceptably low, especially when compared to the costs of switching and the benefits of access to US cloud software and servers. For all these reasons, US hyperscalers’ share of the European market for cloud services will likely remain stable in 2026; any transition to European alternatives will take time.

- As geopolitical tensions increase, Europeans will continue to argue over the meaning of ‘sovereign cloud’ in 2026.

The term ‘sovereign cloud’ does not have an officially agreed definition. In October 2025, the EU Commission corporate IT service (DGIT) put forward a framework for identifying sovereign clouds. This included an 8-point definition and a scientific-looking formula for assigning each service an exact sovereignty score. Yet it is uncertain how these criteria will apply to different cloud models, such as the EU-US partnerships discussed above or the hyperscalers’ own sovereign offerings. In any event, the Commission’s framework is intended for public procurement by EU institutions – not for the wider private sector.

In 2020,ENISA, the European agency for cybersecurity, prepared a draft cloud certification scheme (‘EUCS’) under the Cybersecurity Act, which could be used more broadly. In 2024, a leaked version suggested that the scheme’s highest level of assurance would provide criteria for ‘sovereign cloud’. Yet as of late 2025, development of the scheme remains mired in uncertainty and endless discussions. Separately, in June 2025, the European Parliament called on the Commission to define sovereign cloud in its forthcoming proposal for a Cloud and AI Development Act (‘CADA’), which the Commission is expected to publish in the first half of 2026. This will likely lead to further debates, including in the negotiations between the European Parliament and Council.

At heart, the impasse reflects a broader disagreement over what objectives a European sovereign cloud should achieve. On the one hand, some favour a risk-based approach. This focuses on reducing the risk of foreign government access or interference through effective technical and organisational measures, such as encryption or local back-ups. Such measures can be applied regardless of a cloud provider’s nationality. By contrast, others advocate for a strict approach that uses European cloud providers only, as part of a ‘EuroStack’. This aligns with the EU’s industrial policy aim to strengthen Europe’s cloud sector and support a local industrial base, which can have broader economic benefits. A stronger European cloud sector might, in turn, strengthen Europe’s strategic autonomy, by reducing its reliance on the US and strengthening its ability to act independently on the world stage.

Member States are split between these approaches: the Nordics, Baltics, and the Netherlands appear to favour risk-mitigation strategies, while the French strongly support the strict European-only option.These deeper policy rifts are unlikely to be resolved in 2026; instead, EU institutions will paper over the cracks with compromise solutions. In the meantime, Member States may pursue their own national policies, especially for data-rich and heavily regulated sectors, including financial services, healthcare, and other critical national infrastructure.

- While policymakers dither, European organisations will experiment with different sovereign cloud solutions in 2026.

Public-sector organisations will lead the way in adopting alternatives to the US hyperscalers. The International Criminal Court (‘ICC’) in The Hague provides a clear example. In 2025, the US Government imposed sanctions on ICC Prosecutors and Judges, which prevented the targeted individuals from using Microsoft cloud services. In response, the ICC will transition away from Microsoft to OpenDesk, an open-source suite of office applications developed with funding from the German government. The Danish Ministry for Digitisation is reportedly also experimenting with open-source alternatives. This makes sense, since public-sector organisations need to maintain their independence from foreign governments. For example, given the current geopolitical tensions over Greenland, the Danish government will want to manage the risks of technological dependencies on US service providers.

Similar developments are underway in the German State of Schleswig-Holstein, the French city of Lyon, and the Austrian Army and Ministry of the Economy. The more geopolitical turbulence, the more European public sector bodies will seek to safeguard their independence. The same applies to European providers of critical national infrastructure, as well as organisations that conduct cutting-edge research in sensitive areas that might be of interest to foreign governments. Several Dutch universities are also experimenting with European alternatives, to protect their data from foreign government access.

However, some fear that there are no realistic European alternatives to the US hyperscalers. Miguel De Bruycker, director of the Centre for Cybersecurity in Belgium, recently lamented that it was “impossible” to store data fully in Europe because US companies dominate digital infrastructure. Part of the challenge is that US hyperscalers offer convenient suites of managed services that cover everything from access and identity systems and security measures such as logging and monitoring to relational databases. By contrast, many European providers traditionally focused on offering cloud infrastructure for storage and compute, without the additional managed services. As Bert Hubert put it, the difference is between offering customers wood or ready-made furniture. While wood offers customers more control, furniture is much more convenient. And any customer who is used to the comforts of ready-made furniture is unlikely to switch to woodworking.

Yet this challenge also presents opportunities in 2026. European cloud providers, like T-Systems and OVHcloud, have partnered with Broadcom to offer its VMware software stack of modern cloud services, running on European-owned infrastructure. Further, European companies like Sopra Steria and Schwarz Digits can act as sovereign systems integrators, helping European organisations turn European cloud infrastructure into fully functional IT systems. Alternatively, European customers who already use US clouds can turn to European providers of sovereign middleware, such as Arqit or eXate, who help protect data in use from access by US cloud providers by combining advanced encryption, confidential computing, and pseudonymisation measures.

Lastly, NATO provides an interesting alternative. The 32 Members of the Alliance need a modern cloud-based infrastructure to share information and maintain a tactical edge over adversaries. Yet, European armies cannot simply process classified information in a US cloud, given the risk of US government access or interference. In November 2025, NATO opted to use Google Distributed Cloud air-gapped. This offers a Google cloud software environment which runs on NATO’s isolated infrastructure and which is disconnected from Google. Simply put: Google provides the software; NATO operates the hardware. Broadcom similarly offers ‘VMware Private AI’: a software stack which a European organisation can run on its own infrastructure and use for AI inferencing with an AI model of their choice. IBM recently announced its ‘Sovereign Core’ offering, which offers a similar solution based on customer infrastructure.

These types of ‘in-house’ solutions will not suit all European organisations, as they require the customer to manage its own hardware securely, which requires technical skills and capital expenditure. Indeed, a purist might question whether this is really a ‘cloud’ service at all. In short, such solutions might suit sophisticated and well-resourced organisations, including large companies and public sector institutions, but would be less suited to smaller organisations, who may need to rely local sovereign cloud providers instead. But it illustrates how a range of different cloud models is emerging to address the European demand for sovereign clouds.

These experiments with European sovereign cloud solutions will be closely watched in 2026. Ideally, a more diverse cloud ecosystem will emerge, as different organisations adopt different models. This could improve overall resilience, since Europe would no longer be putting all its eggs in three hyperscale baskets. It would also give European organisations more choices when deploying cloud technology, while reducing foreign governments’ ability to snoop on European citizens or threaten European institutions with a kill switch to cut off access to the cloud. And that would be a promising outcome for 2027 and beyond.

Johan David Michels researches cloud computing law for the Cloud Legal Project at the Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London. He recently co-authored an article on sovereign cloud policy for the Virginia Journal of Law and Technology and has written extensively on related GDPR compliance issues. The Cloud Legal Project is made possible by the generous financial support of Microsoft. The author is also grateful to Broadcom for providing research funding, including to conduct a series of expert interviews and prepare an independent report on sovereign cloud. Responsibility for views expressed remains entirely with the author and do not necessarily reflect views shared by Broadcom.